Into the Missile Storm: The Final Mission of Maj. Thomas Waring Bennett, Jr.

In December 1972, during Operation Linebacker II, Major Thomas Waring Bennett, Jr., a decorated B-52 bomber pilot, flew into the most dangerous airspace of the Vietnam War and did not return, giving his life in the war’s final days.

December 23, 2025

Some wars end not with silence, but with thunder.

Some wars end not with silence, but with thunder.

In December 1972, that thunder came from high above North Vietnam — carried on the contrails and shockwaves of B-52 Stratofortresses flying into the most heavily defended airspace of the Cold War. It was a sound meant to compel an enemy back to the negotiating table, but it was also the sound of young airmen accepting almost unimaginable risk. Major Thomas Waring Bennett, Jr. was one of the men who flew straight into it.

Major Bennett served as a bomber pilot with the 22nd Bomb Wing (TDY), 307th Strategic Wing, under Strategic Air Command — the elite force tasked with nuclear deterrence and, in Vietnam’s final days, conventional strategic bombing at a scale unseen since World War II. For his skill, courage, and extraordinary achievement in aerial flight, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross with Oak Leaf Cluster. That recognition was not ceremonial. It was earned in one of the most dangerous and unforgiving forms of aerial combat ever undertaken.

the elite force tasked with nuclear deterrence and, in Vietnam’s final days, conventional strategic bombing at a scale unseen since World War II. For his skill, courage, and extraordinary achievement in aerial flight, he was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross with Oak Leaf Cluster. That recognition was not ceremonial. It was earned in one of the most dangerous and unforgiving forms of aerial combat ever undertaken.

From December 18 to December 29, 1972, the United States launched Operation Linebacker II, the final, maximum-effort bombing campaign of the Vietnam War. The mission demanded that B-52 crews fly predictable routes, at fixed altitudes, on precise timing intervals — directly into dense belts of North Vietnamese surface-to-air missiles. It was the largest heavy bomber offensive since 1945. It was also the most lethal.

Major Bennett did not return.

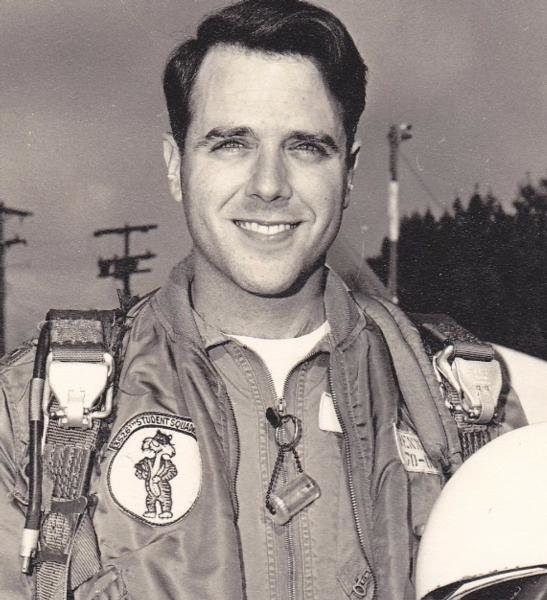

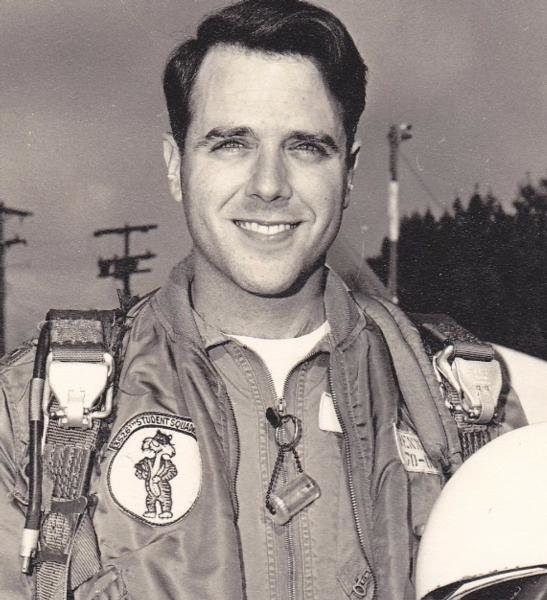

The Man Behind the Rank

Thomas Waring Bennett, Jr. was part of a generation shaped by the Cold War — men who trained for a nuclear conflict they hoped would never come, while being called upon to fight a conventional war that dragged on year after year. By the time he was flying combat missions over North Vietnam, Bennett was no novice aviator. Strategic bomber pilots were among the most rigorously trained airmen in the U.S. Air Force, selected not only for flying skill, but for discipline, judgment, and the ability to function under sustained pressure.

B-52 crews were not lone pilots chasing glory. They were tightly integrated teams: pilot, copilot, radar navigator, navigator, electronic warfare officer, and gunners — each man responsible for a piece of the aircraft’s survival and the success of the mission. When a Stratofortress crossed the coastline into North Vietnam, every crewman knew that no single person could save the aircraft alone. Survival depended on trust, coordination, and adherence to the plan.

Major Bennett was entrusted with command responsibilities in that environment. His Distinguished Flying Cross with Oak Leaf Cluster speaks not only to a single act, but to repeated demonstrations of courage and professionalism under combat conditions. It marks him as an airman who had already faced danger and returned — until the mission that did not allow a return.

The Strategic Gamble of Linebacker II

By late 1972, the Vietnam War had entered its final, bitter phase. Peace talks in Paris had stalled. The Nixon administration sought a decisive action that would force North Vietnam to accept terms and end the conflict. The result was Linebacker II — a concentrated bombing campaign aimed at military, industrial, and logistical targets in and around Hanoi and Haiphong.

What made Linebacker II unique was not only its scale, but its method. B-52s were designed to deliver nuclear weapons against the Soviet Union, not to penetrate layered air defenses over a small, heavily defended country. Yet they were chosen precisely because of their payload, range, and psychological impact.

North Vietnam understood this. Over years of war, they had built the most sophisticated air defense network outside the Soviet Union: radar-guided SA-2 Guideline missiles, anti-aircraft artillery, fighter interceptors, and a command-and-control system refined through experience. By December 1972, Hanoi was ringed with missile sites.

The cost was expected. The losses were accepted before the first aircraft launched.

Flying into the Missile Belts

For B-52 crews, a Linebacker II mission was a study in controlled exposure to danger.

Takeoff often began from Andersen Air Force Base on Guam or U-Tapao in Thailand. Hours of flight passed in formation, with crews reviewing checklists, threat briefings, and emergency procedures. As they approached the target area, electronic warfare systems came alive — jammers humming, warning receivers scanning for radar locks.

Then came the missile launches.

SAMs rose from the ground in blinding streaks, arcing upward at supersonic speed. Crews counted launches, called them out, executed prescribed maneuvers — limited though they were — and relied on electronic countermeasures to break radar locks. There was no dogfighting, no evasive freedom. The B-52 was a massive aircraft, committed to its course, carrying bombs that had to be delivered on precise timing.

If a missile detonated close enough, the shockwave could tear the bomber apart. If fragments severed control lines or ignited fuel, there was often no time to escape.

During Linebacker II, North Vietnamese forces fired more than 1,200 surface-to-air missiles. Fifteen B-52s were destroyed. Crews were killed, captured, or vanished in hostile territory.

Major Thomas Waring Bennett, Jr. was among those losses.

The Moment of Loss

Major Bennett did not fall in a swirling dogfight or above jungle canopy. He was lost in the thin air above Hanoi and Haiphong — where strategy, sacrifice, and steel collided at 30,000 feet.

where strategy, sacrifice, and steel collided at 30,000 feet.

The precise final moments of many B-52 crews remain fragmented, reconstructed from radar plots, radio transmissions, and postwar accounts. What is known is that when a Stratofortress was struck, events unfolded with brutal speed. Crews who escaped did so in seconds, often through fire and disintegrating structure. Others never had the chance.

Major Bennett was one of 33 B-52 crewmen killed or missing in action during Linebacker II — airmen who accepted the mission knowing the risks, knowing the odds, and knowing that turning back was not an option.

For Strategic Air Command crews, refusal was unthinkable. These were missions built on absolute commitment. The men who flew them understood that deterrence, strategy, and national resolve were being measured in real time — and that their lives were part of that calculus.

Distinguished Flying Cross with Oak Leaf Cluster

The Distinguished Flying Cross is awarded for heroism or extraordinary achievement in aerial flight. An Oak Leaf Cluster signifies that the recipient earned the decoration more than once — a testament to repeated exposure to combat danger and sustained excellence under fire.

In Major Bennett’s case, the award  reflects not a single dramatic moment, but a pattern of service: flying into hostile airspace, executing missions despite enemy defenses, and returning to fly again. It speaks to the unglamorous heroism of bomber crews — men who rarely saw the enemy, yet faced some of the deadliest threats of the war.

reflects not a single dramatic moment, but a pattern of service: flying into hostile airspace, executing missions despite enemy defenses, and returning to fly again. It speaks to the unglamorous heroism of bomber crews — men who rarely saw the enemy, yet faced some of the deadliest threats of the war.

To earn such recognition in the final days of Vietnam is to stand among a small fraternity of airmen whose service helped shape the war’s conclusion, even as it claimed their lives.

The Cost of Ending a War

Operation Linebacker II achieved its strategic objective. Within weeks, North Vietnam returned to the negotiating table. The Paris Peace Accords were signed in January 1973. American combat involvement in Vietnam came to an end.

But the cost was borne by men like Major Bennett and his fellow crewmen.

They did not live to see the ceasefire. They did not walk off the flight line into peacetime. Their war ended in the dark sky over North Vietnam, amid missile flashes and contrails.

For the families they left behind, there was no strategic victory — only loss. For their comrades, there was the hollow knowledge that the mission succeeded, but at a price paid by friends who never returned.

Strategic Air Command’s Final Sacrifice in Vietnam

Strategic Air Command was built to deter global nuclear war, yet its Vietnam experience stands as one of its most costly conventional chapters. Linebacker II tested SAC doctrine, equipment, and personnel in ways no exercise ever could.

Major Bennett’s service represents that final cost — paid by bomber crews who were asked to do something their aircraft were never originally designed to do, against defenses specifically built to destroy them.

It was a mission that demanded precision without flexibility, courage without escape, and obedience in the face of overwhelming danger.

Remembering Major Thomas Waring Bennett, Jr.

Today, Major Thomas Waring Bennett, Jr. is more than a name in a casualty list or a line in an after-action report. He was a pilot, a crew commander, a decorated airman — and one of the last Americans to give his life in the skies over Vietnam.

His service embodies the closing chapter of a long and painful war. He flew when the mission demanded everything. He did not turn away. He accepted the risks that strategy required and paid the ultimate price.

At Ghosts of the Battlefield, we preserve these stories not as abstractions, but as human legacies — reminders that wars are ended not only by treaties and negotiations, but by men who climb into aircraft knowing they may not come back.

Major Bennett flew into history on a contrail of fire and resolve.

He will not be forgotten.