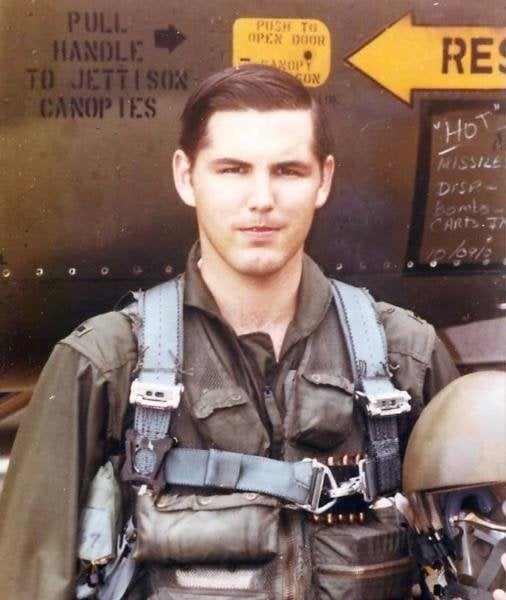

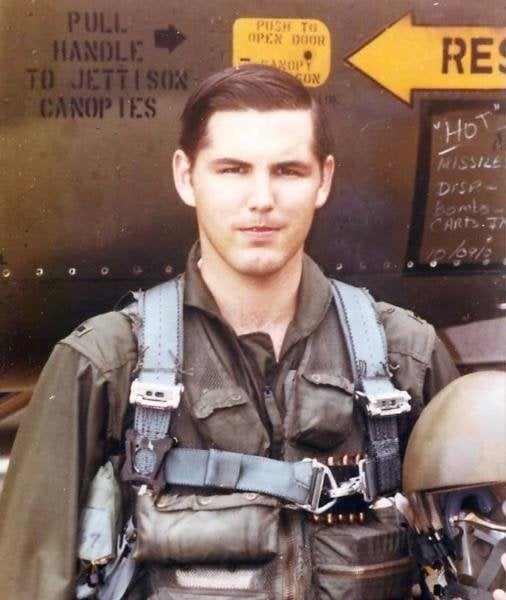

Final Mission of 1LT William Wallace Bancroft Jr.

14th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron, Udorn Royal Thai Air Base November 13, 1970

November 13, 2025

Introduction

Introduction

The Vietnam War relied heavily on information — the movement of enemy units, the construction of new defensive positions, the flow of supplies into hidden sanctuaries, and the shifting patterns of troop activity along the Ho Chi Minh Trail. But before satellites, drones, and digital mapping, information came from men who flew into the heart of danger with cameras instead of weapons. These were the U.S. Air Force reconnaissance crews, the unarmed flyers who entered hostile skies so others could fight with clarity.

Among them was First Lieutenant William Wallace Bancroft Jr., a reconnaissance systems officer whose final mission on November 13, 1970, remains a powerful testament to duty, courage, and sacrifice.

Early Life and Service Path

William Wallace Bancroft Jr. came from a generation shaped by Cold War tensions and a deep sense of national responsibility. Like many young men drawn to the challenge of aviation, he possessed a calm, analytical mind and a willingness to tackle demanding roles. His decision to join the U.S. Air Force placed him on a path that required both intellectual discipline and physical courage.

After commissioning as an officer, Bancroft entered one of the most technically rigorous fields in the Air Force — reconnaissance systems operations. The role demanded proficiency in navigation, radar interpretation, timing, threats analysis, and photographic intelligence. It required the ability to operate under high stress and at high speed, often at low altitude and in hostile airspace.

Bancroft thrived in this environment. His skill earned him assignment to the 14th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron, a combat-proven unit operating out of Udorn Royal Thai Air Base.

The 14th Tactical Reconnaissance Squadron

By 1970, the 14th TRS was one of the most heavily tasked reconnaissance units in Southeast Asia. Their missions ranged from tracking troop movements to mapping supply networks, confirming bomb damage, and photographing newly placed anti-aircraft batteries. Every major bombing campaign, every search-and-rescue operation, and every ground maneuver depended on the imagery they collected.

Their motto, often repeated across the tactical reconnaissance community, summed up their reality:

Alone, unarmed, unafraid.

They flew without missiles or guns, relying only on speed, altitude, terrain masking, and electronic countermeasures to survive. Losses were inevitable.

Yet night after night, the squadron launched missions deep into North Vietnam — because the war could not be fought blind.

The Aircraft: RF-4C Phantom II

The aircraft flown by Bancroft and Wright on that November night was the RF-4C, the premier tactical reconnaissance platform of the war. Unlike the fighter-bomber versions of the Phantom, the RF-4C carried no offensive weapons. Instead, its equipment included:

• High-resolution optical cameras

• Low-light and infrared sensors

• Side-looking radar

• Terrain-following navigation systems

• Electronic countermeasures for self-defense

Its only true defense was speed. At low altitude, the Phantom was remarkably agile, but the risk remained enormous. A single 23mm or 57mm anti-aircraft shell could destroy the aircraft instantly. Surface-to-air missiles, radar-guided guns, and small-arms fire saturated nearly every valley.

Reconnaissance crews understood the risk every time they strapped in.

Mission Context: Rising Activity in Ha Tinh Province

During early November 1970, intelligence analysts detected increased North Vietnamese logistics traffic in Ha Tinh Province. Newly placed anti-aircraft guns had appeared along transport routes. Truck convoys were moving supplies under the cover of night. The United States needed confirmation — photographic evidence.

This became the task of Wright and Bancroft.

Their mission plan required a night low-level penetration into one of the most heavily defended sectors of North Vietnam. The terrain in Ha Tinh was notoriously difficult: steep ridges, sharp valleys, dense vegetation, and narrow river paths that left little margin for error. The danger was compounded by the fact that night missions removed the advantage of visibility while intensifying the threat from radar-controlled antiaircraft positions.

But reconnaissance crews were accustomed to danger. This was not a mission anyone forced on them — it was the work they chose.

November 13, 1970: The Final Flight

Shortly after nightfall, Major David I. Wright and 1LT William Bancroft boarded their RF-4C. The jet taxied from its revetment, engines vibrating through the metal shielding walls. Ground crewmen performed their final checks and signaled the aircraft forward.

With full afterburner, the Phantom surged down Udorn’s runway and climbed into the darkness.

Their route took them across Laos, through mountain passes and into North Vietnam. At the navigation station, Bancroft coordinated timing, altitude, and camera operations. The pair descended deeper into the valleys east of Tan Ap, preparing for their photographic run.

In the darkness, an explosion lit the sky.

North Vietnamese witnesses later described a fireball and debris scattering across the ridgeline. Intelligence analysts believed the aircraft may have been struck by anti-aircraft fire or a missile. The RF-4C disintegrated in midair.

No parachutes were seen. No radio calls were made.

The aircraft was lost instantly.

Missing in Action

Back at Udorn, the aircraft failed to make its scheduled radio calls. Radar showed only the last point before the Phantom vanished. By dawn, the crew was officially listed as Missing in Action.

Search and rescue teams could not reach the area. It was too deep inside enemy territory, surrounded by heavily fortified anti-aircraft networks.

For days, uncertainty weighed heavily on the men of the 14th TRS.

On November 18, 1970, intelligence sources confirmed the fate of the crew. Major Wright and First Lieutenant Bancroft had been killed in the crash.

The squadron mourned. They had lost not only fellow airmen, but part of the small community of specialists who performed some of the most dangerous flying of the war.

Decorations and Medals Earned by 1LT Bancroft

Based on his service record, mission category, and standard awards given to Air Force aviators killed in action during this period, 1LT Bancroft received the following decorations (I can adjust or expand if you have his DD-214 or official award list):

• Distinguished Flying Cross

• Air Medal (with one or more oak leaf clusters for multiple combat missions)

• Purple Heart

• National Defense Service Medal

• Vietnam Service Medal (with campaign stars based on dates served)

• Republic of Vietnam Campaign Medal

• Air Force Outstanding Unit Award

• Air Force Longevity Service Award

• Marksmanship Ribbon (if completed qualification)

He may have additional decorations related to unit citations, training accomplishments, or campaign service — I can build a complete formal medal list if provided with his service number or citation sheets.

Legacy of Sacrifice

First Lieutenant William Wallace Bancroft Jr. represented the highest standards of the U.S. Air Force. His missions were performed without fanfare, recognition, or the protective firepower offered to other types of aircraft. He flew into danger not to destroy but to reveal — to gather the intelligence that shaped operations across the entire theater.

The loss of Bancroft and Wright was not in vain. Their work helped build the operational picture that allowed U.S. forces to respond effectively to enemy activity. Their sacrifice is part of the broader legacy of reconnaissance crews who risked everything so that commanders could make informed decisions.

More than fifty years later, the courage shown by these airmen continues to resonate in the histories preserved by museums, memorials, and dedicated researchers who refuse to let their stories fade.

Remembering 1LT William W. Bancroft Jr.

Today, his name stands among those who gave their lives in service to their country. For the families, friends, and communities who knew him, the loss was profound and permanent. For future generations, his story serves as a reminder that the cost of freedom is not always found in the most publicized battles, but often in the quiet, unseen missions carried out by men like Bancroft.

generations, his story serves as a reminder that the cost of freedom is not always found in the most publicized battles, but often in the quiet, unseen missions carried out by men like Bancroft.

At Ghosts of the Battlefield, his legacy is preserved not only in historical record but in the collective memory we keep alive. His final mission is more than a tragic line in a casualty report — it is a story of bravery, professionalism, and dedication to a mission that shaped the broader course of the war.

1LT William Wallace Bancroft Jr. stepped into the night so others could see. His sacrifice remains part of the enduring shadow cast by the Vietnam War and the men who served with honor until their final breath.