The Long Road from Fort Monroe: Major George H. Crawford, Bataan, and a Message Returned Too Late

Clinging to that hope, Helen mailed him a simple postcard on January 1, 1945. “This will be our year.”

January 7, 2026

The Long Road from Fort Monroe: Major George H. Crawford, Bataan, and a Message Returned Too Late

Before war carried him across the Pacific, George H. Crawford served quietly at Fort Monroe, standing watch at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay. Fort Monroe was a place of preparation—of drills, orders, and the steady movement of officers passing through its gates on their way to distant assignments. It was here, in Hampton Roads, that Crawford wore the uniform in a nation still at peace, even as the world beyond its shores was already burning.

When orders came for the Philippines, they carried no promise of glory. They carried urgency.

War Comes to the Philippines

On December 8, 1941—just hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor—Japanese aircraft struck American airfields in the Philippines. The U.S. Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE), composed of U.S. Army units, Philippine Scouts, and newly mobilized Philippine Commonwealth divisions, were suddenly fighting for survival. Outmatched in air power, short on equipment, and facing a seasoned enemy, American commanders ordered a strategic withdrawal to the Bataan Peninsula under War Plan Orange.

The plan had always been grim: hold Bataan long enough for reinforcements to arrive. Those reinforcements never came.

Major Crawford was among the officers shepherding exhausted men through collapsing lines as the fighting retreated westward. Roads clogged with refugees. Supply dumps burned to prevent capture. Hospitals overflowed. Food dwindled. Malaria, dysentery, and beriberi spread faster than replacements could arrive.

The Bataan Timeline: A Retreat Measured in Weeks and Losses

December 1941 – Early January 1942

Following initial engagements in northern and southern Luzon, U.S. and Filipino forces began falling back toward Bataan. Units fought delaying actions at road junctions and river crossings, buying time at terrible cost. Men marched by night, fought by day, and slept in the rain when they could.

January 7–22, 1942: Abucay–Mauban Line

The first major defensive line across Bataan ran from Mauban to Abucay. Here, American and Filipino units resisted repeated Japanese assaults. Fighting was close, often hand-to-hand in jungle terrain. Despite determined resistance, flanking maneuvers and infiltration forced a withdrawal.

January 26 – February 8, 1942: Orion–Bagac Line

A second line was established farther south. Conditions worsened. Daily rations fell to starvation levels. Ammunition shortages became critical. Still, the line held—longer than anyone had believed possible.

February – March 1942: Stalemate and Attrition

Japanese attacks slowed, but disease and hunger ravaged the defenders. Men collapsed at their posts. Hospitals lacked medicine, bandages, even food. Officers like Crawford were forced to make impossible choices: who could still fight, who could be carried, who would be left behind.

April 3–9, 1942: Final Offensive and Surrender

A massive Japanese assault shattered the weakened lines. With no food, no medical support, and no hope of relief, U.S. forces were ordered to surrender on April 9, 1942.

It has long been believed that Major Crawford’s unit was among the very last to lay down their arms—holding out until resistance was no longer physically possible. If true, it was not defiance for its own sake, but duty carried to the final moment.

Capture and the Beginning of Captivity

Capture and the Beginning of Captivity

The surrender did not bring mercy. It brought the Bataan Death March.Tens of thousands of American and Filipino prisoners were forced to march north under brutal conditions. Those who fell were beaten or shot. Water was denied. Bodies lined the roads. Survival depended on chance, endurance, and the will to keep moving one step at a time.

Major Crawford survived the march and the months that followed. Survival, however, did not mean safety. POW camps in the Philippines were places of constant hunger, disease, and abuse. Prisoners labored on starvation rations, living with the knowledge that many of them would never see home again.Yet somehow, Crawford endured.

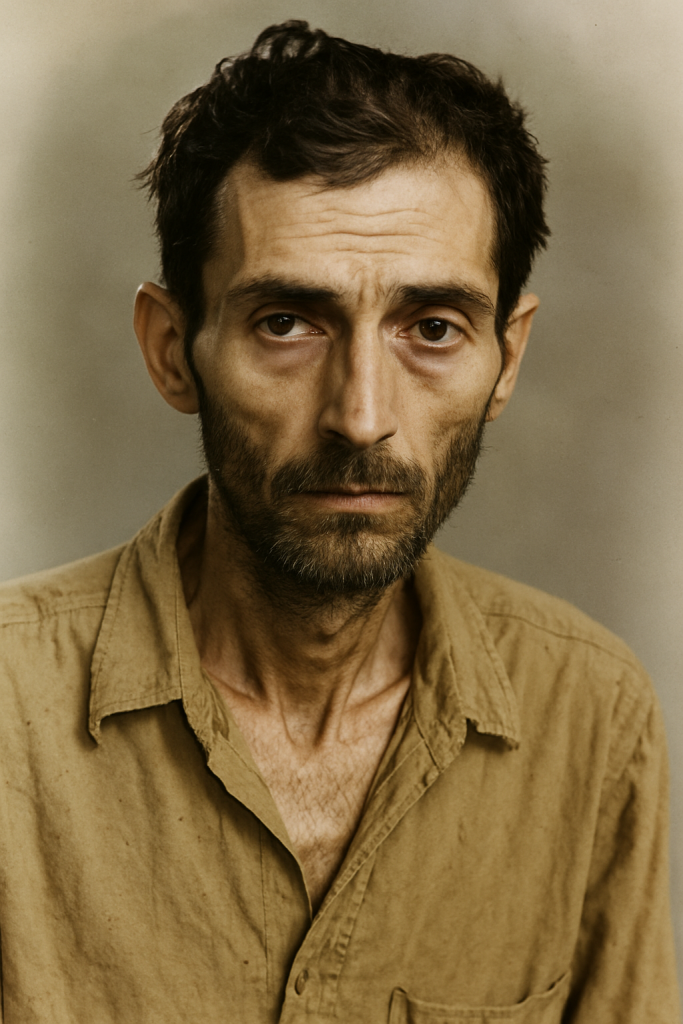

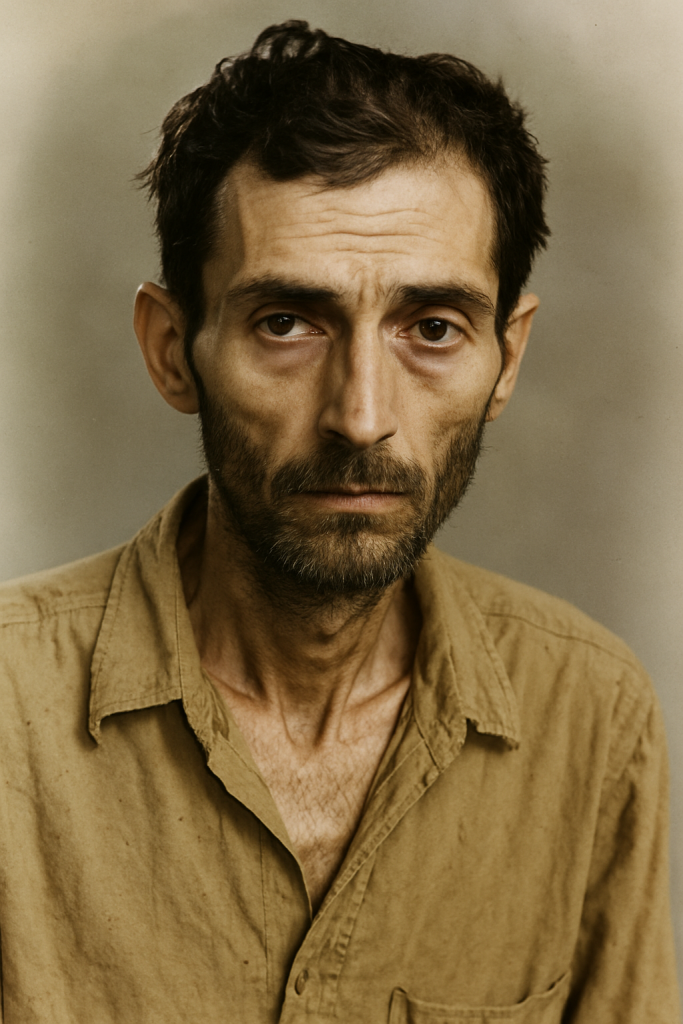

Using our powerful software we can bring to life how Major Crawford may have looked in those harrowing three years.

News Reaches Home

On New Year’s Day 1944, Helen Crawford received a telegram from the War Department: her husband had been captured and was now a prisoner of war in the Philippines. It was a message steeped in dread—but also one that left room for hope. He was alive. Somewhere.For wives of POWs, time did not move normally. Days stretched into months. Silence became routine. Every knock at the door carried fear. Every envelope was opened with shaking hands.

Helen waited.

The Hell Ships

By late 1944, American forces were returning to the Philippines. Japanese authorities began evacuating POWs to the home islands and occupied territory using cargo vessels known today as “hell ships.” These ships were unmarked, overcrowded, and brutal. Prisoners were crammed into holds with little air, little water, and no medical care.

On December 15, 1944, Major Crawford was among 1,620 Allied prisoners forced aboard the Oryoku Maru at Manila.

The ship carried Japanese troops and military supplies alongside POWs. It bore no markings to indicate it carried prisoners. When U.S. Navy aircraft spotted the convoy in Subic Bay, they saw only a legitimate enemy target.

They attacked.

Bombs struck the Oryoku Maru (The ship burns in the photo right). Fires spread. The ship began to sink. Prisoners trapped below decks drowned, burned, or were killed by explosions. Others were shot or beaten as they attempted to escape. More than 200 prisoners died that day.

Bombs struck the Oryoku Maru (The ship burns in the photo right). Fires spread. The ship began to sink. Prisoners trapped below decks drowned, burned, or were killed by explosions. Others were shot or beaten as they attempted to escape. More than 200 prisoners died that day.

Major George H. Crawford was one of them.

A Hope Rekindled—Then Crushed

Helen did not know.

Weeks after the sinking, she received another telegram from the War Department stating that her husband had been transported on a later ship—suggesting he had survived the attack. Hope returned, fragile but alive. Perhaps he was still somewhere, still waiting.

Clinging to that hope, Helen mailed him a simple postcard on January 1, 1945.

“This will be our year.”

“This will be our year.”

It was not a grand message. It did not speak of strategy or sacrifice. It spoke of reunion. Of survival. Of faith in a future that still felt possible.

But George was already gone.

Months later, sometime in the summer of 1945, the truth finally emerged. The earlier information had been wrong. Major Crawford had perished on December 15, 1944, aboard the Oryoku Maru.

And then, more than a year after his death, on January 14, 1946, Helen’s postcard came back—returned by the War Department. Undeliverable.

A message of hope, sent across an ocean, to a man who would never read it.

What Remains

Today, at Ghosts of the Battlefield, Major George H. Crawford’s last worldly possessions rest on display. They are modest things. Personal things, letters to and from home, a photo and his medals. Objects that survived when he did not.

They represent a life that moved from Fort Monroe to Bataan, from command to captivity, from endurance to loss. They also represent something else—the cost of war measured not only in battles fought, but in years of waiting, in letters never answered, in hope sustained until it could no longer be held.

The Battle of Bataan is remembered for its heroism, its suffering, and its endurance against impossible odds. But its legacy does not end on the peninsula or on the Death March roads. It extends into living rooms and kitchens across America, into the lives of wives like Helen Crawford who waited through silence and misinformation, who held on through years of uncertainty, and who learned the truth only after hope had been allowed to bloom one last time.

At Ghosts of the Battlefield, we remember not only the men who fought and died—but those who waited. We remember that war does not end when the guns fall silent. Sometimes, it ends when a postcard comes back stamped undeliverable.

Major George H. Crawford’s story is not only one of service and sacrifice. It is a reminder that behind every uniform is a family, behind every casualty is a lifetime interrupted, and behind every artifact is a human story that deserves to be told—carefully, honestly, and never forgotten.

Capture and the Beginning of Captivity

Capture and the Beginning of Captivity