Signed “Good Luck Flag” – 寄せ書き日の丸 (Yosegaki Hinomaru)

Eevery brushstroke carries the weight of a nation at war. This yosegaki hinomaru, signed for soldier Toshio Yoshikawa and carried home by Sgt. Lynn Hazelbaker, speaks with the voices of both Japan’s farewell and America’s victory.

September 13, 2025

A Flag That Speaks for a Nation at War

A Flag That Speaks for a Nation at War

This is not merely a flag. It is the voice of a community, a farewell gift to a young Japanese soldier named Toshio Yoshikawa (吉川敏雄) as he marched into the uncertain shadows of war. In Japan during the Second World War, such banners—known as 寄せ書き日の丸 (Yosegaki Hinomaru)—were given to soldiers departing for the front. They were signed by family members, friends, schoolmates, and workplace colleagues. Each signature and phrase inscribed on the white field surrounding the red sun carried with it a wish for survival, a reminder of home, and an expectation of loyalty and sacrifice.

For Yoshikawa, this cloth was more than a piece of the national flag. It was a protective charm, a spiritual shield, and a symbol of the hopes and demands of an entire community. Today, it survives as a haunting relic of a society mobilized for total war.

Words Written in Ink and Spirit

Across the fabric of Yoshikawa’s flag, bold calligraphy commands the eye. These inscriptions reveal not only personal hopes but also the collective resolve of wartime Japan.

-

On the left, the phrase 「武運長久」(Buun Chōkyū) invokes a prayer: “May your fortune in battle be long-lasting.” This was one of the most common blessings written on yosegaki flags, expressing the universal wish that the soldier would return alive and victorious.

-

At the top, a more strident declaration: 「撃ちして止まむ米英」, translated as “We shall not cease fighting until America and Britain are defeated.” This reflects the fierce national determination of Japan’s war years, when slogans of resistance against the Allied powers were widely promoted.

-

Elsewhere, slogans of loyalty and sacrifice are inscribed in bold strokes: 「忠君愛国」(Chūkun Aikoku), meaning “Loyalty to the Emperor and love for the nation,” and 「盡忠奉公」(Jinchū Hōkō), “Give your life in service to the Emperor and country.” Another variation, 「盡忠報国」(Jinchū Hōkoku), emphasizes sacrifice for the defense of the homeland.

These were not casual phrases. They were the ideological backbone of wartime Japan, binding individuals to the Emperor, to the nation, and to the collective destiny of a people at war.

Yet alongside these patriotic declarations, more personal and intimate words appear. At the lower right corner, one hand wrote: 「御友を戦友にて待つは」 – “Awaiting the day when dear friends will be welcomed as comrades-in-arms.” This phrase reveals the human face of war: friendships transformed into promises of solidarity on the battlefield, personal bonds reshaped by the demands of military service.

A Community’s Handwriting

The yosegaki hinomaru was not the gift of a single person, but of an entire community. Families, classmates, teachers, company supervisors, and neighbors all contributed their signatures. In this way, the flag represented more than just the soldier—it symbolized the unity of home and nation behind him.

This practice reflected Japan’s system of 総力戦 (Sōrikusen, “total mobilization”), in which every aspect of civilian life was drawn into the war effort. Factories, schools, and villages were expected to provide both material support and moral encouragement to those sent to the front lines. The yosegaki flag, with its mixture of patriotic slogans and personal messages, embodies this reality.

From Battlefield to Souvenir

From Battlefield to Souvenir

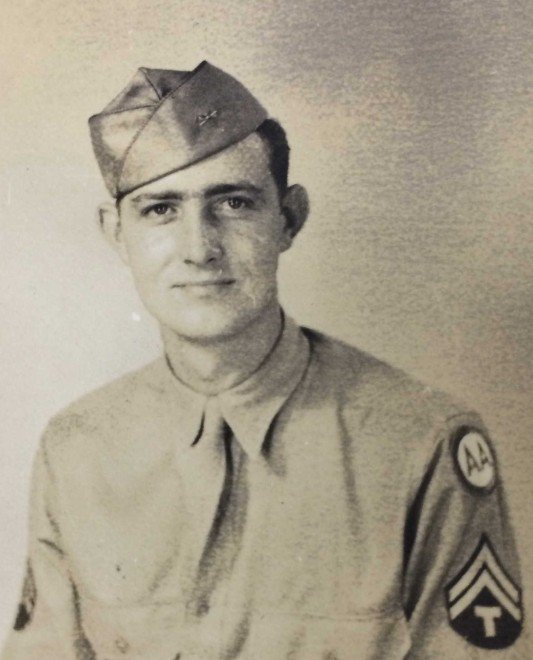

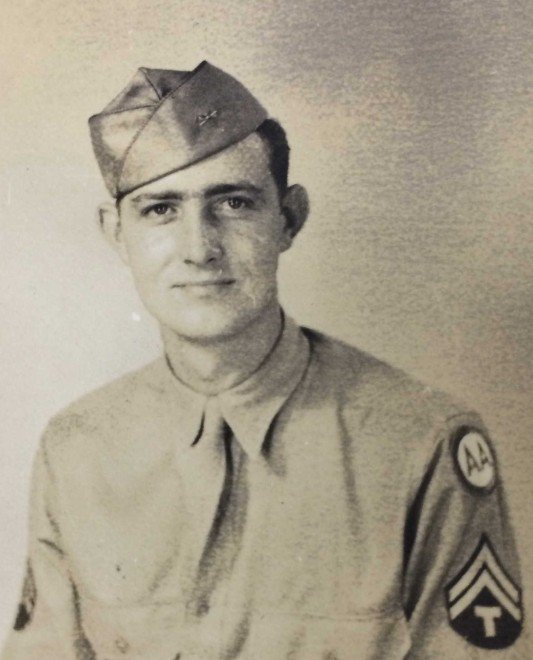

The story of Yoshikawa’s yosegaki hinomaru does not end with him. Like many battlefield relics, it was carried back across the Pacific as a war souvenir. This particular flag became the possession of Sgt. Lynn Hazelbaker of the 233rd Anti-Aircraft Searchlight Battalion, a U.S. Army unit that provided illumination and air defense during the Pacific campaigns.

For Hazelbaker, the flag was likely a memento of service, a tangible reminder of the enemy he and his comrades faced. For decades after the war, such flags were displayed in American homes, kept in attics, or passed down through families. They carried with them the memory of victory, but also the silent testimony of the Japanese soldiers who once owned them.

Today, the flag is displayed alongside other wartime artifacts that Sgt. Hazelbaker brought back from the Pacific. These include rank patches cut from Japanese uniforms, occupation currency from territories under Japanese control, and the original envelope in which the yosegaki hinomaru was mailed home. Together, these objects form a small but powerful collection that speaks to Hazelbaker’s service, his encounters with the enemy, and the tangible ways soldiers remembered and preserved their wartime experiences.

What the Flag Means Today

Today, the yosegaki hinomaru has taken on a new meaning. Once intended as a talisman of survival for Yoshikawa, it has become a relic of history, a cultural artifact that speaks across time.

It tells us about the soldier who carried it, the family and friends who signed it, the nation that demanded his loyalty, and the American serviceman who brought it home. It speaks to the reality of total war, where entire communities inscribed themselves into the fabric of combat.

For visitors, this flag is not simply an artifact under glass. It is a voice—a voice of a soldier departing, of a society mobilized, of families hoping and fearing, and of a war that touched lives on both sides of the Pacific.

The yosegaki hinomaru of Toshio Yoshikawa, preserved by Sgt. Lynn Hazelbaker, stands today as a powerful testament to World War II’s human dimension. More than cloth, more than ink, it is a story woven in handwriting, memory, and sacrifice.

It is, in every sense, a flag that speaks.

From Battlefield to Souvenir

From Battlefield to Souvenir