Ghosts of the Rising Sun: The Story of a Yosegaki Hinomaru

A simple flag, inked with prayers and signatures, became a soldier’s shield as he marched into the chaos of war. Yet behind its folds lies a haunting silence—we do not know who Iinuma Tatsuo was, whether he survived, or what role he played.

August 27, 2025

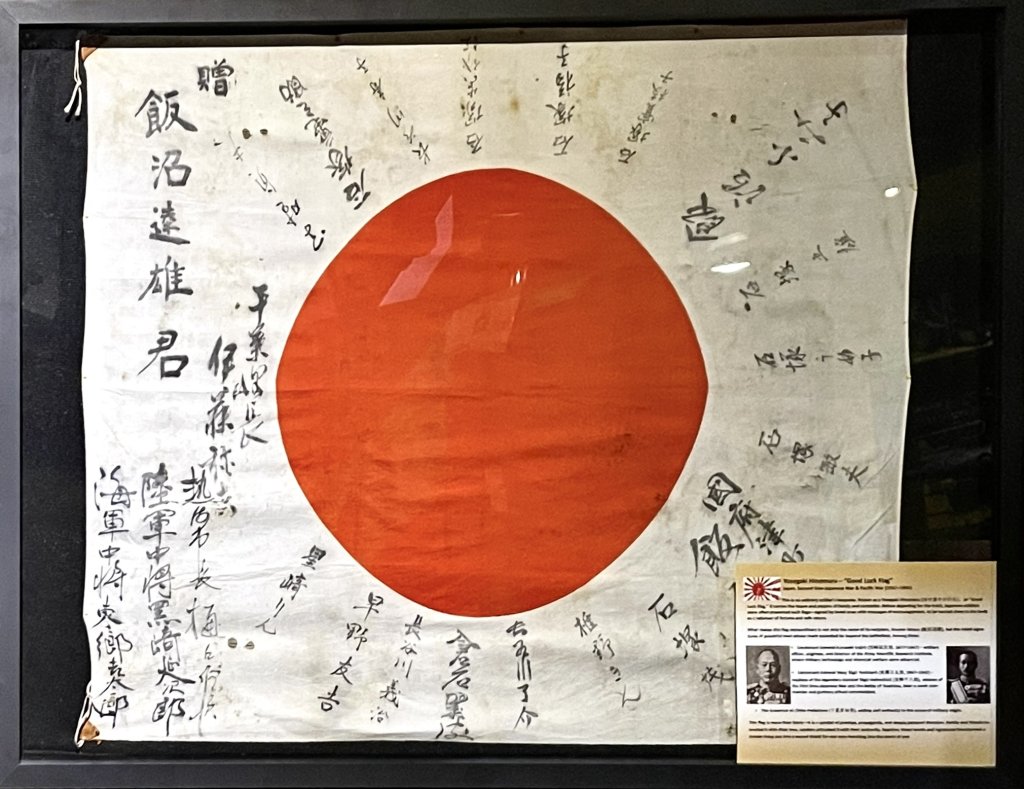

During the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Pacific War (1937–1945), Japanese soldiers often departed for the front carrying a sacred keepsake known as a Yosegaki Hinomaru (寄せ書き日の丸) — a “Good Luck Flag.” Family members, friends, and neighbors would gather to inscribe their names and words of encouragement across the white field of the Rising Sun, their inked prayers intended to guard the soldier in battle and ensure a safe return. These flags were folded and kept close to the body, becoming both a talisman and a tangible reminder of home.

During the Second Sino-Japanese War and the Pacific War (1937–1945), Japanese soldiers often departed for the front carrying a sacred keepsake known as a Yosegaki Hinomaru (寄せ書き日の丸) — a “Good Luck Flag.” Family members, friends, and neighbors would gather to inscribe their names and words of encouragement across the white field of the Rising Sun, their inked prayers intended to guard the soldier in battle and ensure a safe return. These flags were folded and kept close to the body, becoming both a talisman and a tangible reminder of home.

The flag preserved in our collection bears the name of its recipient, Iinuma Tatsuo (飯沼達雄), but what sets it apart is the distinguished company among the signatures. Intermixed with the blessings of family and acquaintances are the names of some of Japan’s most powerful figures.

And yet, despite the prominence of these signatories, the soldier at the heart of this story remains a mystery. Beyond his name, almost nothing is known of Iinuma Tatsuo. Did he march into China in the late 1930s, or was he sent to the Pacific islands later in the war? Did he ever see home again, or did this flag perhaps return without him, a silent memorial to a life lost in battle? The historical record does not say.

What endures is this flag — a fragile piece of cloth heavy with the weight of hope, authority, and unanswered questions. Its survival allows us to glimpse both the personal and political forces that shaped Japan’s war effort, while also reminding us of the countless soldiers like Iinuma Tatsuo whose stories remain untold, their destinies swallowed by the chaos of war.

What makes this flag extraordinary is not only the name of its recipient, Iinuma Tatsuo (飯沼達雄), but the inked signatures of powerful men whose reach extended far beyond the battlefield. Among them:

Lieutenant General Kurosaki Enjirō (黒崎延次郎, often read Nobujirō in Japanese sources; 1877–1967) was an Imperial Japanese Army artillery officer-turned–technical leader whose career bridged the line between ordnance engineering and state–industry weapons research. Born in today’s Takanezawa, Tochigi, he graduated the Imperial Japanese Army Academy (1897) as an artillery second lieutenant and later completed electrical engineering at Tokyo Imperial University (1908), an unusual academic credential that steered him into the Army’s technical bureaucracy. He served in key posts at the Osaka Artillery Arsenal and the Army Technical Headquarters, rising to lieutenant general in 1927. In 1928 he became director of the Army Scientific Research Institute (Rikugun Kagaku Kenkyūjo), the IJA’s central hub for military technology and chemical-warfare R&D. Wikipedia

Under Kurosaki’s tenure, the Institute coordinated with private industry on “dual-use” chemical programs. Archival studies note that in December 1928 the Army transmitted instructions both to Hodogaya Soda’s managing director and to “Army Scientific Research Institute Director, Lt. Gen. Kurosaki Enjirō,” setting out technical guidance and reporting lines for ethylene production—part of the Army’s broader push to secure liquid chlorine and precursors for chemical agents while expanding civilian bleach and chemicals markets. This program framework fed directly into Japan’s interwar chemical-weapons capability.

Placed on the reserve list in 1932, Kurosaki remained influential in Manchuria’s armaments build-up. That July he was appointed head of an ordnance arsenal survey mission that helped lay the groundwork for Manchukuo’s arms-production system; he subsequently served as representative director of the Fengtian Ordnance Works company and held posts with Manchukuo industrial concerns and the Fengtian Chamber of Commerce.

Vice Admiral Tōgō Kichitarō (often rendered Yoshitarō, 東郷吉太郎, 1867–1942) was a career officer of the Imperial Japanese Navy and the nephew of the famed Fleet Admiral Tōgō Heihachirō, hero of Tsushima. Born in 1867, he graduated from the 13th class of the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy in 1886 and quickly proved himself in the gunnery branch, serving as a division commander aboard the gunboat Yoshino and corvette Takao during the First Sino-Japanese War. Over the following decade he held successive gunnery officer assignments on the cruisers Takachiho and Hashidate, earning promotion to lieutenant commander in 1898. By 1899 he was chief gunnery officer aboard the battleship Fuji, and in 1900 he traveled to Great Britain to help commission a new vessel for Japan, returning the following year. His career advanced steadily into the 20th century, and although his precise combat role in the Russo-Japanese War is less clearly recorded, his rank and expertise make it likely he participated in the fleet actions of that conflict, including the famed Battle of Tsushima under his uncle’s command. Rising ultimately to the rank of vice admiral—a naval equivalent of lieutenant general—Tōgō Kichitarō capped his service with senior command and instructional posts, including leadership of the Naval Gunnery School, before retiring in the interwar period. He died in 1942, remembered as a capable and technically skilled officer who carried forward the Tōgō naval legacy into a new generation.

Even the Governor of Chiba Prefecture (千葉県知事) left his mark, lending the prestige of civilian authority to this soldier’s send-off.

This Yosegaki Hinomaru was therefore much more than a simple good-luck charm. It embodied the devotion of family, the encouragement of comrades, and the endorsement of the state’s highest ranks. To the man who carried it, the flag was a sacred shield, a living testament that he marched into war with the voices of both loved ones and leaders at his side.

Based on the dates and the prominent military signatories, we believe that Iinuma Tatsuo likely served in China during the late 1930s, a time when Imperial Japan’s armies advanced deep into Chinese territory. The conflict there was brutal, stretching from the Marco Polo Bridge Incident of 1937 into a drawn-out war marked by devastation and suffering. Japanese forces committed widespread atrocities against civilians, most notoriously during the Rape of Nanking, where tens of thousands were massacred and women suffered systematic sexual violence. Countless other acts of brutality unfolded across occupied regions, leaving scars that remain part of China’s national memory to this day.

In this light, the flag becomes more than a personal artifact — it is also a window into the contradictions of war. To Iinuma and his family, it was a talisman of protection, a vessel of love and hope. Yet to those caught under the shadow of the empire he served, the same rising sun could symbolize fear, destruction, and oppression. Its survival offers us today not only a reminder of devotion and national identity in wartime Japan, but also a sobering connection to the darker realities of a conflict that claimed millions of lives.