The Odenwald Incident: The Last Prize of the U.S. Navy

Two U.S. warships patrolling the South Atlantic stumbled upon a freighter flying American colors. What followed — a desperate chase, a daring boarding, and the capture of a disguised German blockade runner — became the final “

November 6, 2025

The Odenwald Incident: The Last Prize of the United States Navy

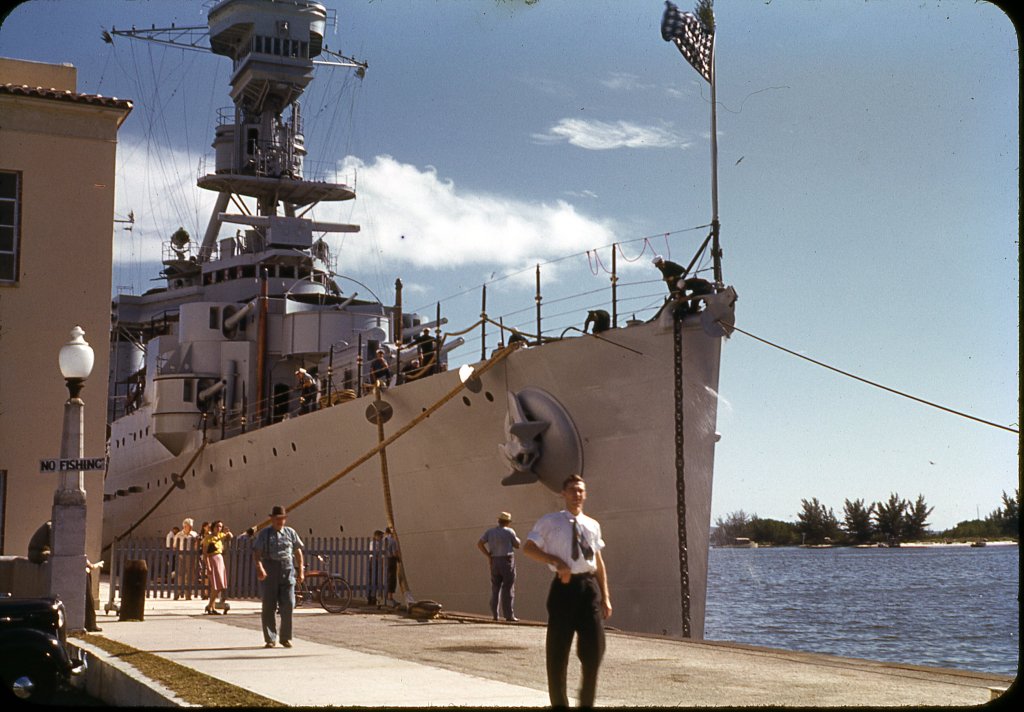

The morning sun over the Atlantic was a dull, humid smear of gold and haze — a deceptive calm that hid the world’s rising fury. It was November 6, 1941, and the USS Omaha (CL-4), a light cruiser of the U.S. Navy’s Neutrality Patrol, cut steadily through the tropical waters off the coast of Brazil. The ocean shimmered with that deceptive serenity sailors know well — the kind that comes just before something unexpected breaks the horizon.

America was not yet officially at war. But everyone aboard the Omaha could feel it: the tension, the coded radio reports, the whispered word from Washington that German U-boats were prowling ever closer, testing the patience of a nation still clinging to neutrality. President Roosevelt’s orders were clear — protect the Western Hemisphere, enforce neutrality, and shadow any ship that might be supplying the Reich.

That morning, the lookout in the Omaha’s foremast spotted smoke — a thin gray column against the blue. As the ship closed in, the silhouette of a freighter took shape on the horizon. She flew the U.S. flag and bore the name Willmoto painted neatly across her stern. Her homeport, it appeared, was Philadelphia.

But something wasn’t right.

Commander Theodore R. Dunlap, Omaha’s commanding officer, studied the ship through his binoculars. The lines of her hull, the mast arrangement, the way she rode low in the water — none of it quite matched any American freighter he knew. He ordered Omaha’s course adjusted and signaled the destroyer USS Somers (DD-381), operating nearby, to close the range.

The Omaha’s 6-inch guns trained slowly toward the stranger. A signal light blinked across the waves: “Identify yourself.”

For a long moment, there was no reply. Then, almost too quickly, came a flashing answer: “U.S. freighter Willmoto, Philadelphia.”

Dunlap frowned. The Willmoto, according to U.S. registry, should have been thousands of miles away. Something was off. He ordered Omaha to battle stations and dispatched a warning shot — a single shell that splashed into the sea ahead of the freighter’s bow.

What happened next shattered any doubt about the ship’s true identity.

The freighter’s crew began abandoning ship — lifeboats splashing into the water, sailors scrambling down ropes, smoke pouring from her hatches. The “American” vessel was on fire. It was an act of self-destruction — the desperate, deliberate scuttling of a ship caught in the act.

Dunlap wasted no time. “Prepare a boarding party!” he barked. Boats were lowered into the churning wake. Armed sailors from the Omaha and Somers, led by Lieutenant George K. Carmichael, rowed hard toward the burning vessel, the acrid smell of smoke and oil growing thicker as they approached.

When they reached the side, Carmichael could see the deception up close: beneath hastily painted “Willmoto” markings, traces of another name bled through. The letters “O-D-E-N…” were just visible through the gray paint.

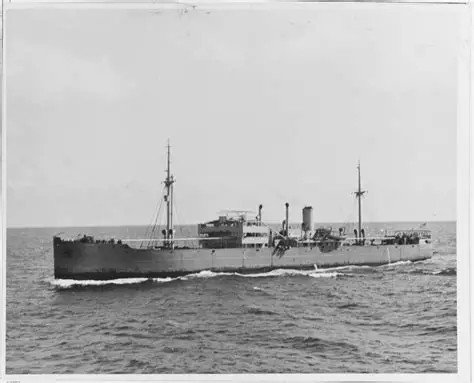

This wasn’t a U.S. freighter at all. It was the German blockade runner Odenwald, operating under false colors and attempting to slip through the Allied blockade with a cargo of raw rubber, tin, and other vital war materials from Japan — all bound for occupied France.

Carmichael and his men clambered up the Jacob’s ladder, weapons ready. The decks were deserted, the air hot with the smell of burning insulation. Below decks, they found charges set to blow the ship apart, the sea valves open, and water gushing in. The Germans had tried to sink their own vessel rather than let it be captured.

The Americans raced against time. Plugging leaks, slamming hatches, and fighting fires, they struggled for hours to save the Odenwald. Through the smoke and chaos, they managed to bring the engines under control and close the sea valves. Against all odds, they stabilized her. The ship was wounded but afloat.

By sunset, the Stars and Stripes flew from her mast — replacing the false American flag she had used as disguise. The Odenwald was now in U.S. custody, the first German prize taken by the Navy in the Atlantic since the days of the Civil War.

The Omaha and Somers escorted their captured quarry northward. The journey was tense. No one knew whether German U-boats might try to avenge the loss or whether diplomatic chaos would erupt once news reached Berlin. After all, the United States was still, at least on paper, a neutral nation.

The Omaha and Somers escorted their captured quarry northward. The journey was tense. No one knew whether German U-boats might try to avenge the loss or whether diplomatic chaos would erupt once news reached Berlin. After all, the United States was still, at least on paper, a neutral nation.

When the convoy reached San Juan, Puerto Rico, the story broke across the Navy wires — an American warship had seized a German blockade runner before war had even been declared. Newspapers blared the headlines: “NAVY CAPTURES GERMAN BLOCKADE SHIP IN ATLANTIC.” The Odenwald’s cargo — thousands of tons of strategic rubber — was worth a fortune.

At first, the Roosevelt Administration walked a delicate line. Officially, the Navy had acted under its Neutrality Patrol authority. The Germans, having disguised their ship as American and attempted self-destruction, had forfeited any claim of innocence. But everyone understood what the incident truly meant.

The United States was no longer merely a neutral observer. The “Neutrality Patrol” had become a de facto combat operation, shadowing, intercepting, and sometimes firing upon Axis vessels. The Odenwald incident joined a string of escalating confrontations that autumn — from the torpedoing of the destroyer USS Greer, to the attack on USS Kearny, and the loss of USS Reuben James, all before Pearl Harbor.

The Atlantic was already a battlefield in all but name.

The Odenwald’s Cargo

When Navy investigators opened the Odenwald’s hatches, they found her holds packed tight with rubber bales and other high-value materials critical to the German war machine. Japan, though not yet formally at war with the United States, was already funneling strategic resources to its Axis ally through neutral or disguised shipping.

Rubber was among the most precious commodities of the war. It was essential for tires, aircraft parts, seals, and gaskets — everything a modern military required. Germany’s own supply had been cut off by the British naval blockade, forcing them to rely on clandestine blockade runners like Odenwald to keep production alive.

The value of her cargo was estimated at more than $3 million (about $60 million today).

When the ship was finally brought safely into port, the legal question became immediate: What did it mean for a “neutral” navy to seize an enemy ship? Could her crew be prisoners? Could her cargo be claimed as prize?

The U.S. government sidestepped the diplomatic trap by classifying the Odenwald as “salvage” rather than an act of war. Because her crew had abandoned her, the Americans argued, the vessel was derelict and therefore subject to maritime salvage law — a subtle distinction that kept Washington from technically violating neutrality while rewarding the men who had risked their lives to save her.

The Boarding Party’s Reward

For the sailors of the Omaha and Somers, the Odenwald affair would soon take on a life of its own in legal and naval history. The crew filed a claim in U.S. District Court seeking a share of the ship’s value under the ancient maritime principle of “salvage rights.”

The court agreed.

The men who had boarded and saved the Odenwald were entitled to salvage money, a rare and nearly forgotten tradition dating back to the days when privateers captured enemy vessels for profit. The court’s final ruling awarded the crew a total of $3,000 in prize shares — divided among the boarding party, officers, and crew based on rank.

For the sailors involved, the money was small compared to the pride of the act. They had, quite literally, captured an enemy ship on the high seas, prevented its destruction, and preserved valuable evidence of Axis deception. But in doing so, they also closed a chapter in naval tradition.

The Odenwald would be the last ship in U.S. history for which American sailors received such prize or salvage money. The ancient practice of paying crews for captured vessels would quietly fade into history, replaced by the modern understanding that wartime actions were matters of national service, not private reward.

The Shadow War at Sea

To understand how extraordinary the Odenwald capture was, it helps to remember how close the U.S. already stood to open war in the fall of 1941.

That September, a U-boat had fired on USS Greer south of Iceland, prompting Roosevelt’s famous “shoot-on-sight” order: any Axis warship found in waters vital to American security would be treated as hostile. Weeks later, USS Kearny was torpedoed while escorting a convoy — eleven American sailors were killed. On October 31, USS Reuben James was sunk outright by a German U-boat, taking more than 100 men to the bottom.

The Atlantic was no longer neutral.

The Odenwald, sailing under false U.S. markings, symbolized the growing lawlessness of that twilight period — a global chessboard where disguise, deception, and secret cargoes blurred the line between peace and war.

When word of the capture reached Germany, the Nazi press denounced it as piracy. The American public, however, largely applauded the Omaha’s crew. In editorial pages across the country, the message was clear: our Navy was already fighting — we just hadn’t declared it yet.

The Ship’s Fate

The Odenwald herself was towed to Puerto Rico and then to the U.S. mainland. After being processed as a captured vessel, she was officially turned over to the War Shipping Administration and rechristened USS Blenheim, later serving under the U.S. Merchant Marine during the war.

Her days as a blockade runner were over. Instead, she carried supplies for the Allies — a remarkable turn of fate for a ship that had once tried to slip through the blockade she now helped enforce.

The Men Behind the Moment

The official reports from that day read like dry logs — times, coordinates, and signals exchanged. But behind those words were men acting under immense pressure, risking their lives in what was still, technically, peacetime.

Lieutenant George K. Carmichael, who led the boarding party, later recalled that they could hear the sea rushing in through the open valves and smell the gunpowder from the scuttling charges. He and his men waded waist-deep through rising water, groping in the smoke-choked engine room to find and close the valves before the ship went down. Their quick action saved the Odenwald from sinking and prevented an environmental disaster in the mid-Atlantic.

Commander Theodore Dunlap, commanding officer of the Omaha, was later commended for his leadership and judgment. His calm but firm handling of the situation — ordering the warning shot, organizing the rescue, and avoiding unnecessary escalation — demonstrated the professionalism that defined the Navy’s Neutrality Patrol in those perilous months before Pearl Harbor.

The destroyer USS Somers and her crew, too, played a vital supporting role — covering the operation, standing ready for possible submarine attack, and assisting in the escort northward.

A Nation on the Brink

By the time the Odenwald arrived safely in San Juan, the world had changed. Just one month later, on December 7, 1941, Japanese aircraft roared over Pearl Harbor, dragging the United States into full-scale war.

When Roosevelt declared that America was now “in a state of war,” few aboard the Omaha or Somers were surprised. They had already felt its presence in the Atlantic swells, in the gray mist where disguised freighters and lurking submarines played deadly games of cat and mouse.

The Odenwald’s capture, in hindsight, stands as a prelude — a warning flare fired into history’s darkening storm. It was proof that the oceans were no longer neutral, that the time for half-measures had passed, and that the world’s last great democracy would soon have to fight for its survival.

The Legacy

Today, the Odenwald incident is remembered as both a legal curiosity and a symbolic turning point. Legally, it marked the final invocation of prize law in American naval history — the last time sailors would be financially rewarded for capturing an enemy vessel. But morally and strategically, it revealed something deeper about the character of the Navy on the eve of war.

Those sailors did not act for money. They acted out of duty, discipline, and instinct — preserving life, property, and honor in a gray zone where orders were unclear and danger omnipresent. Their capture of the Odenwald didn’t just save a ship; it helped expose the scope of Axis deception and underscored that America’s “neutral” Atlantic patrols were already an undeclared front in World War II.

In a way, the Odenwald was the first Axis ship taken by American hands — a quiet but undeniable step from neutrality toward engagement, from isolation to involvement, from peace to war.

The men of the Omaha and Somers could not have known, as they watched that false-flag freighter smolder in the tropical sun, that within weeks they would be part of a nation at war across two oceans. But they did know what every sailor feels in his bones — that the sea has no patience for illusions, and that neutrality, like calm water, never lasts forever.

In the fading twilight off Brazil, as the captured freighter rolled gently in the swell and the Stars and Stripes fluttered in the humid wind, one chapter of American naval tradition ended and another began.

The Odenwald became the last prize of the United States Navy — and the first warning shot of a world soon engulfed in fire.