The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal: The Night the Pacific Turned

The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal (Nov. 12–15, 1942) was a fierce series of night fights where U.S. ships stopped Japan from retaking the island. Despite heavy losses, America held Henderson Field and turned the tide of the Pacific War.

November 13, 2025

The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal: The Night the Pacific Turned

Few nights in naval history were as savage, intimate, and decisive as those fought in the inky waters off Guadalcanal between November 12 and 15, 1942. A campaign that had already raged for months on land, in the air, and across the Solomon Sea now reached its turning point. The Japanese Empire, hoping to sweep the Americans from the island once and for all, committed major naval forces to bombard Henderson Field, land reinforcements, and restore the initiative. Instead, in a series of close-quarters clashes—fought at ranges so short that sailors could see the faces of enemy crews in their searchlights—the United States Navy delivered the decisive check to Japan’s ability to project power in the South Pacific.

The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal was not one engagement but several, threaded together by desperation, miscommunication, raw courage, and moments of chaotic brilliance. It was a watershed moment: the first major engagement in which the U.S. Navy stood toe-to-toe with the Imperial Japanese Navy in night combat at equal strength—and won.

This is the story of how that happened.

Prelude: The Long Grind to November

By the fall of 1942, Guadalcanal had become a bleeding ulcer for Japan. What began with the U.S. landings on August 7 had turned into a brutal stalemate. Both sides fed men and ships into the thick jungle and narrow waters, each trying to break the other’s ability to hold Henderson Field—the vital airstrip that let the “Cactus Air Force” dominate the daylight skies.

The Japanese ran nightly “Tokyo Express” destroyer runs down the Slot, rushing troops and supplies under cover of darkness. By day, American aircraft savaged anything that lingered near the island.

By early November, Japan planned a decisive operation: two waves of transports, covered by battleships, cruisers, and elite destroyers, would bombard Henderson Field, land 7,000 troops, and wipe out the Marine and Army defenders.

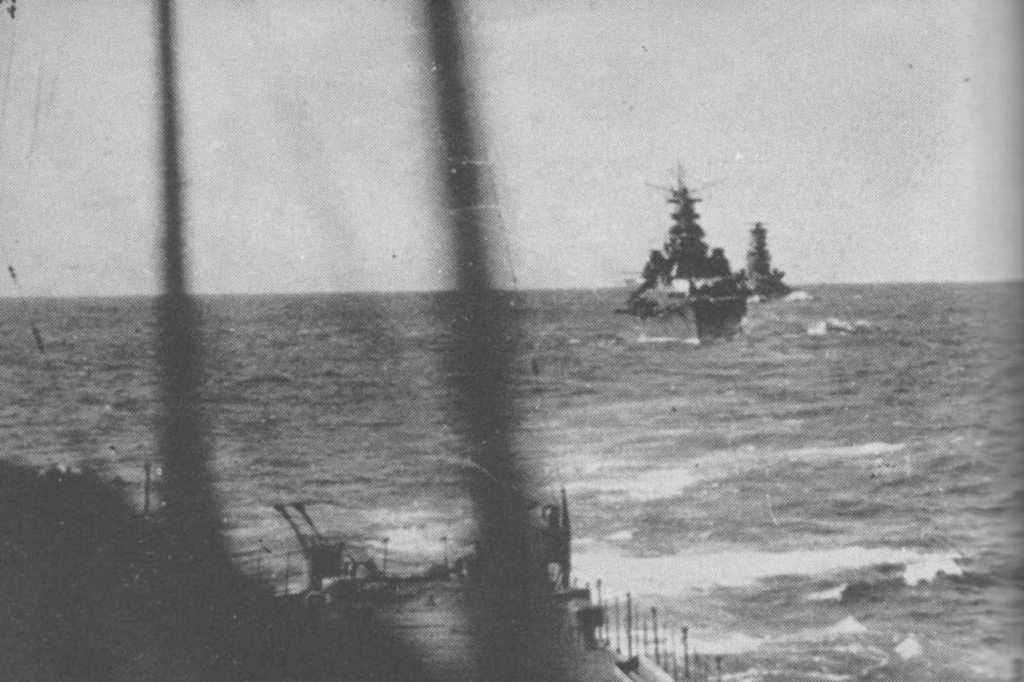

The first bombardment force centered on the battleships Hiei and Kirishima—fast, powerful, and bristling with 14-inch guns that could flatten Henderson Field in minutes.

The Americans, aware something large was coming, scrambled every available ship to intercept. Many were worn, undermanned, or short on officers. Yet they sailed anyway.

November 12: The Opening Moves

On the afternoon of November 12, American and Japanese aircraft clashed over the waters north of Guadalcanal as the first Japanese convoy approached. The transports took damage, but the fight was only a prelude. Both fleets knew the real test would come that night.

American Admiral Daniel Callaghan commanded a force of two heavy cruisers, three light cruisers, and eight destroyers. Crucially, his flagship, USS San Francisco, lacked modern radar. Callaghan chose a battle formation that placed his radar-equipped ships away from the vanguard, a decision that would have enormous consequences.

American Admiral Daniel Callaghan commanded a force of two heavy cruisers, three light cruisers, and eight destroyers. Crucially, his flagship, USS San Francisco, lacked modern radar. Callaghan chose a battle formation that placed his radar-equipped ships away from the vanguard, a decision that would have enormous consequences.

The Japanese bombardment group, under Admiral Hiroaki Abe, steamed south in two columns. They intended to obliterate Henderson Field at daybreak. Instead, they would blunder into a confused, point-blank knife fight.

November 13: The First Night

Shortly after 1:30 a.m., radar aboard USS Helena picked up contacts—many of them. Callaghan hesitated, unsure of the formation, and the Americans plunged directly into the Japanese line.

The result was one of the most chaotic surface battles in naval history.

Destroyers from both sides collided at close range. Searchlights snapped on, illuminating targets only a few hundred yards away. Ships fired at silhouettes, muzzle flashes, or whatever fired at them first. The Japanese battleship Hiei found itself surrounded, taking torpedoes and 8-inch shells from multiple directions. American destroyers like Cushing, Laffey, and Sterett threw themselves into the fight with suicidal aggression, many taking catastrophic hits.

Callaghan and his second-in-command, Admiral Scott, were both killed when enemy gunfire smashed into San Francisco’s bridge. Leadership devolved to ship captains making moment-to-moment decisions amid smoke, fire, and screaming metal.

By 2:30 a.m., it was over. The price was staggering.

The Americans lost two cruisers—Atlanta and Juneau—and four destroyers. But the Japanese had failed to bombard Henderson Field. Hiei, crippled and unable to steer, was pounded by aircraft later that morning and sank—the first Japanese battleship lost in the war.

More importantly, the transports scheduled to land troops had been delayed.

The sacrifice of Callaghan’s task force bought a single, precious day.

November 14: Air Strikes and Desperate Gambles

November 14 was a day of ferocious aerial combat. The Japanese sent another powerful cruiser force—Kumano, Suzuya, Atago, Maya, and others—to bombard the airfield that night. Meanwhile, transports again tried to creep closer.

But daylight belonged to the Cactus Air Force.

Dive-bombers and torpedo planes from Henderson Field, joined by aircraft from the carrier Enterprise, hammered the Japanese. Heavy cruiser Kinugasa was sunk. Several transports were destroyed or set ablaze. Still, many survived and continued south.

But another, much graver threat was coming. The second bombardment force—a powerful group built around the battleship Kirishima—approached under cover of darkness.

Waiting for them was a small, battered American force commanded by Admiral Willis Lee.

Lee brought only two battleships—Washington and South Dakota—and four destroyers. But Washington carried the finest radar in the fleet, and Lee was a gunnery expert who understood night combat.

The stage was set for the second, and most decisive, night action.

November 14–15: The Second Night

At 11 p.m., the American destroyer van charged into the Japanese formation. One by one, they were blown apart, sacrificing themselves to protect the battleships. By midnight, South Dakota entered the fray—alone, illuminated by Japanese searchlights and repeatedly struck by shells that knocked out her electrical systems.

Kirishima and her escorting cruisers poured fire into the glowing silhouette of the battleship. South Dakota, though battered, stayed afloat—but she was blind, deaf, and unable to respond effectively.

Kirishima and her escorting cruisers poured fire into the glowing silhouette of the battleship. South Dakota, though battered, stayed afloat—but she was blind, deaf, and unable to respond effectively.

Then, from the dark, Washington arrived.

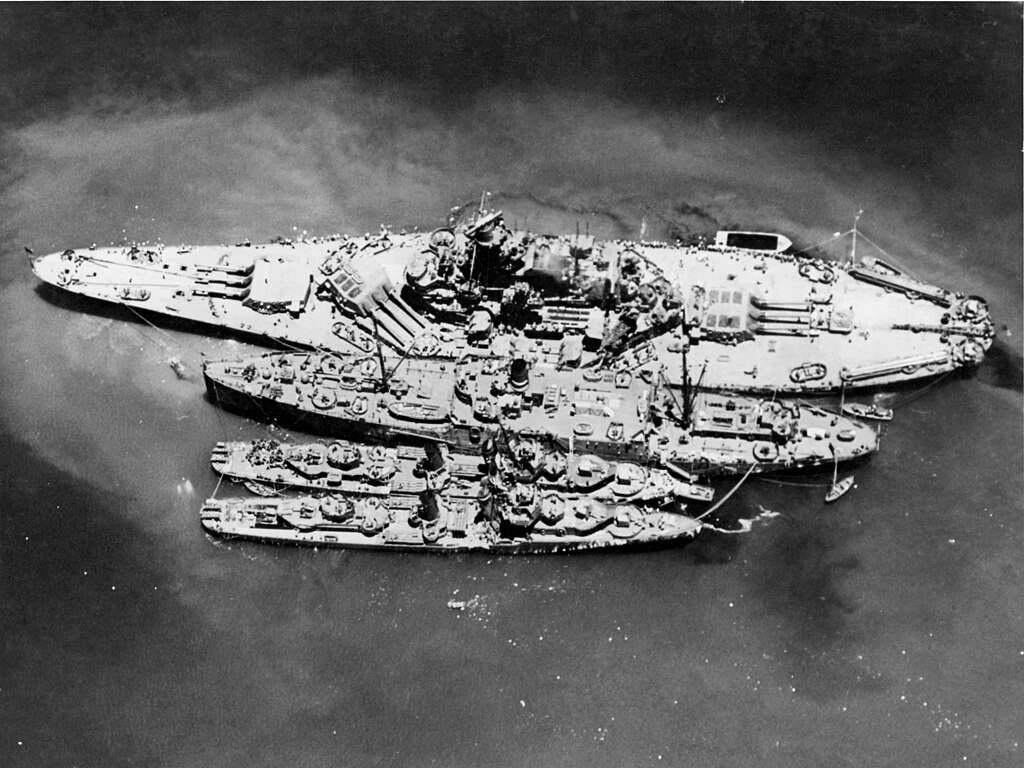

Washington had remained undetected. Her radar-guided guns locked onto Kirishima at 8,400 yards—point-blank range for a battleship. In seven minutes, Washington fired 75 rounds of 16-inch shells and over 100 5-inch shells. Kirishima was ravaged. Fires spread across her decks, her steering jammed, and her crew scuttled her around 3:25 a.m.

The Japanese, stunned by the sudden annihilation of their battleship, withdrew. The transports, deprived of cover, attempted to run themselves ashore in the predawn darkness. American aircraft and artillery shredded them.

Only a fraction of the troops and supplies ever reached land.

Japan’s last major attempt to retake Guadalcanal had failed.

Aftermath: The Turning Tide

When the sun rose on November 15, the waters off Guadalcanal were filled with oil slicks, drifting rafts, burning hulks, and the debris of one of the most violent naval clashes of the Pacific War.

The battle had cost the U.S. Navy two admirals, seven ships, and over 1,700 men. The Japanese had lost two battleships, a heavy cruiser, three destroyers, most of their transports, and thousands of troops either killed or stranded without supplies.

But the strategic implications were even greater.

The Japanese Navy, already stretched thin, could no longer sustain major reinforcement efforts at Guadalcanal. The destruction of so many destroyers crippled their Tokyo Express operations. The loss of Hiei and Kirishima weakened their capital ship strength. And the failure to neutralize Henderson Field left the Americans with uncontested daylight dominance.

In January 1943, Japan began withdrawing from Guadalcanal entirely. The island—once the edge of their defensive perimeter—was now a deadly drain on their resources and manpower.

The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal was the knife point that tipped the balance.

It marked the moment Japan’s offensive momentum finally snapped.

Tactical Lessons: Radar, Training, and Command

Beyond its drama, the battle exposed critical truths about the evolving nature of naval warfare.

-

Radar was a war-winner.

Ships like USS Helena and USS Washington demonstrated the power of radar-guided gunnery and detection. Callaghan’s failure to prioritize radar-equipped ships cost lives. Lee’s mastery of radar tactics won the second night. -

Destroyers were the decisive arm.

American destroyers, often outmatched individually, fought with reckless valor. Their torpedo attacks disrupted Japanese formations and absorbed punishment that would have otherwise found the cruisers and battleships. -

Japanese night-fighting skill remained formidable—but no longer dominant.

Early in the Solomons campaign, Japanese Long Lance torpedoes and superior night optics made them nearly unbeatable after dark. But by November, radar and better American coordination had begun turning the tide. -

Command and control were critical—and vulnerable.

The deaths of Admirals Callaghan and Scott created chaos during the first night’s battle. Meanwhile, Admiral Abe hesitated—failing to use Hiei’s 14-inch guns decisively when he had the chance. -

Courage under fire defined the outcome.

Both sides showed extraordinary bravery. But the American willingness to push damaged ships, to engage at suicidal ranges, and to keep fighting despite losses proved crucial.

Human Stories: Sacrifice in the Dark

The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal is filled with individual acts of heroism.

On Atlanta, sailors fought fires and kept the ship in action even as friendly shells tore through her superstructure. On Juneau, the Sullivan brothers—George, Francis, Joseph, Madison, and Albert—served together until the cruiser was torpedoed and exploded, taking almost her entire crew with her. Their loss would influence U.S. policy on siblings serving together for generations.

On the Japanese side, the crew of Hiei fought for hours to save their stricken ship, even as fires spread from turret to turret. The men of Kirishima struggled to keep her afloat long after the battlelines dissolved.

These personal struggles, often overshadowed by strategy and tactics, form the emotional core of the campaign. In the end, the battle was decided not only by technology, but by sailors—young men, many barely trained—who met each other in the dark with courage and desperation.

Strategic Significance: The First Major American Naval Victory

The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal was more than another clash in the Solomons. It was the first time the U.S. Navy decisively defeated the Imperial Japanese Navy in a major fleet action. Midway had been a turning point—but it was fought largely by aircraft. Here, steel met steel. Here, battleships dueled at ranges unseen in the war so far.

And here, the Japanese saw something they had not seen before: American forces standing firm, refusing to yield, and ultimately driving them from the field despite fearsome losses.

After Guadalcanal, the Japanese Navy shifted to a long, grinding defensive posture. They would win tactical victories in the Solomons, but never again threaten a major strategic offensive.

Guadalcanal marked the beginning of the long rollback that would carry U.S. forces across the Central Pacific, through the Marianas, and ultimately to the doorstep of Japan itself.

Conclusion: The Night the Momentum Broke

For three nights and days in November 1942, the waters off Guadalcanal witnessed some of the most brutal naval combat ever fought. Radar pulses flickered through the darkness. Battleships traded broadsides at ranges closer than most gunnery drills. Destroyers died buying minutes that would change the course of a campaign.

The Naval Battle of Guadalcanal was not clean. It was not elegant. It was raw, chaotic, terrifying, and costly. But it was decisive.

It ensured that Henderson Field would stand. It ensured that the Japanese offensive would fail. And it marked the moment when the U.S. Navy—bloodied, battered, but unbroken—proved it could seize the initiative and hold it.

The Pacific War’s tide shifted in those black waters. And though many of the ships that fought there now rest beneath the waves of Iron bottom Sound, the significance of their sacrifice endures.