The Lesser Known Invasion, Iwon (October–November 1950)

The small fishing town of Iwon lay on North Korea’s northern coast offered a gentle slope and open access for landing craft. It was far from any remaining stronghold of the North Korean.

October 29, 2025

The sea was calm. The beach was empty. Yet the silence of Iwon would echo across the mountains of North Korea.

In the autumn of 1950, the world watched the Korean Peninsula turn on its axis. Only four months earlier, United Nations forces were trapped within a shrinking defensive ring around Pusan. But by October, the same forces were advancing northward with unstoppable momentum. The bold amphibious landing at Inchon had reversed the course of the war, recapturing Seoul and sending the North Korean army into chaotic retreat.

In that surge of optimism and confidence, another landing was planned — one that received little attention, faced no gunfire, and yet revealed everything about the fragile balance between victory and overreach. Its name was Iwon.

A WAR TRANSFORMED

By October 1950, the United Nations Command — made up of troops from the United States, South Korea, the United Kingdom, and several allied nations — believed the end of the war was near.

General Douglas MacArthur envisioned a lightning campaign that would destroy the remaining North Korean People’s Army and reunify the peninsula under Seoul’s government. His orders were bold: advance north of the 38th Parallel, seize control of North Korea’s key ports, and push all the way to the Yalu River — the frontier with China.

On the west coast, the U.S. Eighth Army surged toward Pyongyang. On the east, the X Corps prepared to land further north in support of the advance. The operation called for a two-pronged assault — one at Wonsan, another at Iwon — designed to open new lines of supply and speed the end of the conflict.

For the soldiers who received the orders, it felt like a promise: one last push and the war would be over.

WHY IWON

The small fishing town of Iwon lay on North Korea’s remote eastern shore, about halfway between Wonsan and the Soviet border. Its beach offered a gentle slope and open access for landing craft. It was far from any remaining stronghold of the North Korean army, and that isolation made it perfect for an unopposed landing.

The plan was simple. The U.S. 7th Infantry Division, under the command of Major General David Barr, would come ashore, establish a supply base, and push inland to link with other advancing units. From there, the division would move toward the Yalu River — the ultimate objective of the United Nations advance.

It was a logistical operation as much as a combat one. The landing would deliver men, fuel, food, and ammunition into a barren corner of enemy territory. It was the kind of amphibious movement the U.S. military had perfected during World War II — and now, in Korea, it would be tested again.

THE APPROACH TO IWON

In the days leading up to the landing, the sea lanes were swept for mines. The convoy sailed north through cold gray waters. The men aboard the transports — veterans of World War II now serving in their second conflict — cleaned their rifles, wrote letters home, and tried to imagine what lay ahead.

They had seen combat on the beaches of Saipan, Leyte, and Okinawa. They expected the worst. But as the coastline of North Korea came into view, the scene was almost peaceful.

At dawn on October 29, 1950, the first landing craft began to move toward shore. Engines growled. Waves slapped against steel hulls. The ramps dropped. Soldiers waded into knee-deep water and crossed the sand in perfect silence.

No gunfire. No enemy. No resistance.

It was the most surreal invasion any of them had ever seen.

GREEN BEACH

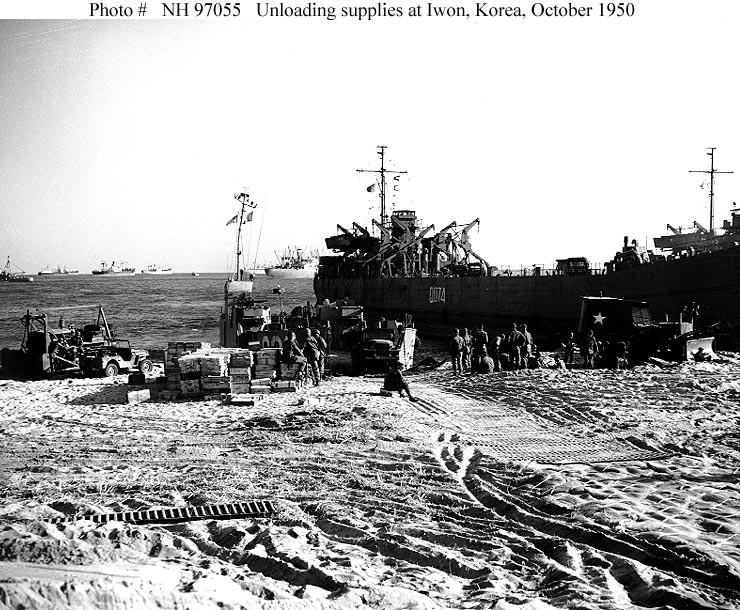

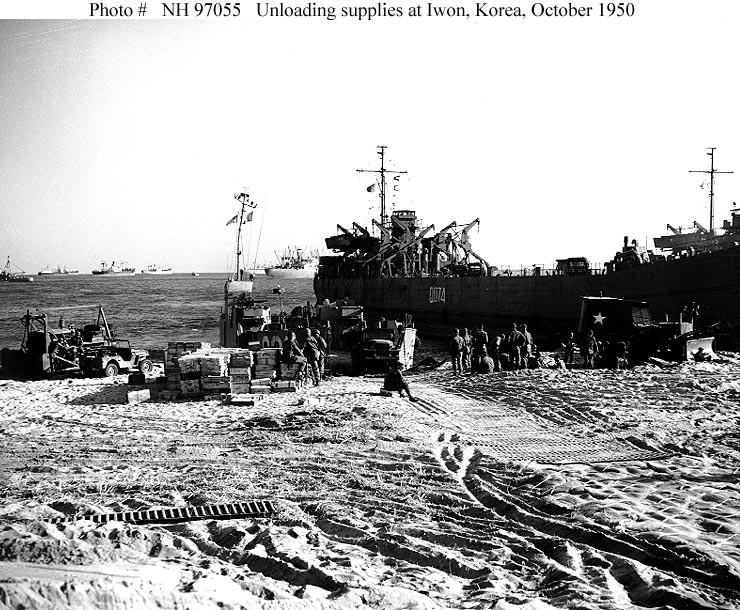

With the landing zone secured, the engineers of the 7th Infantry Division went to work. Bulldozers roared across the beach, pushing mounds of sand into makeshift roads. Troops filled sandbags to create ramps where trucks could roll directly from the landing craft.

The men named the area Green Beach — a nod to the amphibious code colors used in the Pacific War.

Landing ships anchored offshore, lowering their massive doors to unload tanks, jeeps, and crates of supplies. Forklifts and cranes followed. In a few days, Iwon’s quiet shoreline was transformed into a bustling port of war.

Photographs taken during those days show soldiers wearing field jackets against the chill, standing beside lines of trucks that seemed to stretch into infinity. For them, it was work — long, heavy, exhausting work — but it was also a sign that the end of the war might finally be within reach.

THE LONG ROAD NORTH

By the first week of November, the 7th Division began its northward push. The beaches behind them faded into mist as the columns of vehicles climbed mountain roads toward the interior. The deeper they went, the harsher the terrain became. The cold sharpened with each mile.

Villages stood deserted. Roadsides were littered with broken wagons and burned-out trucks. Every sign of battle was in retreat. Prisoners captured along the route confirmed that the North Korean army was disintegrating, retreating toward the Yalu.

Villages stood deserted. Roadsides were littered with broken wagons and burned-out trucks. Every sign of battle was in retreat. Prisoners captured along the route confirmed that the North Korean army was disintegrating, retreating toward the Yalu.

Confidence ran high. The men joked about being home by Christmas. They didn’t know that winter — and a new enemy — was already waiting.

THE EDGE OF THE YALU

On November 21, 1950, a patrol from the 7th Infantry Division reached the Yalu River near Hyesanjin. It was the northernmost point any U.S. ground unit would reach in the war.

The soldiers climbed down the snowy embankment and stared across the frozen water into Manchuria. Some dipped their canteens into the river — a symbolic gesture marking how far they had come. Others simply stood in silence, gazing across the border at the distant mountains.

They didn’t realize that Chinese troops were already crossing those mountains in force, moving silently south in the frozen darkness.

A PERFECT OPERATION, A DANGEROUS LESSON

From a tactical standpoint, the landing at Iwon was flawless. The operation was executed with precision, coordination, and discipline. There were no casualties. No confusion. No enemy interference.

But in the broader view of the war, Iwon revealed the first cracks in the U.N. campaign. The speed and ease of the advance gave commanders the illusion that the enemy was finished. The long supply lines stretching from the southern ports to the far north were fragile, vulnerable to weather, terrain, and ambush.

When the Chinese offensive erupted weeks later, those vulnerabilities became catastrophes.

The same men who had marched triumphantly from Iwon would soon find themselves fighting through blizzards, cut off from supplies, retreating under fire in what became one of the most grueling campaigns in American military history.

THE HUMAN SIDE OF IWON

For the men who were there, the memory of Iwon was defined by contrasts — the beauty of the sea, the silence of the beach, and the looming sense that something unseen was coming.

They remembered unloading heavy crates under pale sunlight that never seemed to warm. They remembered nights when the wind off the sea howled through the tents and froze their canteens solid.

There was no gunfire, no enemy, no medals for bravery — just endless labor and the weight of anticipation. Some later said that the quiet of Iwon was harder to bear than the chaos of battle.

It was too calm. Too easy. Too strange.

A SOLDIER’S MEMORY

Imagine a young soldier standing on that beach, helmet tilted back, rifle slung over his shoulder. The surf rolls in around his boots. Behind him, the landing ships stretch across the horizon like steel islands. Ahead, the mountains rise into the clouds.

He thinks of home — of warmth, of food, of quiet. He believes, like everyone else, that this war is nearly done. But somewhere deep inside, he feels the chill of uncertainty. He doesn’t know it yet, but the cold winds sweeping down from Manchuria carry the sound of a new enemy on the move.

That soldier’s photo might still exist — perhaps faded, tucked into a scrapbook or a footlocker. In that still image, he stands at the hinge point of history: the moment before triumph turns to tragedy.

STRATEGIC IRONY

The irony of Iwon is as sharp today as it was in 1950. It was one of the most successful amphibious operations ever conducted — and one of the least necessary.

By the time the 7th Infantry Division came ashore, the North Korean army in that region was already collapsing. Iwon’s capture added little to the overall campaign. The landing was flawless in execution but redundant in purpose.

Worse, it deepened the illusion that the war was all but over. As divisions spread across the width of North Korea, command and supply became strained. When the Chinese intervention hit in late November, those isolated units — from the Chosin Reservoir to the Yalu frontier — were thrown into chaos.

Iwon became a case study in how perfect planning can still lead to peril.

THE AFTERMATH

Within weeks, the calm beachhead of Iwon became a frozen supply line. The same bulldozers that had built roads through sand now carved paths through snow. Trucks that once carried ammunition now hauled wounded men back toward the sea.

As reports of the Chinese offensive reached the rear, Iwon’s landing zone was repurposed for evacuation and emergency shipments. The optimism that had filled the air in October was gone. By December, the entire peninsula was again engulfed in chaos and retreat.

And yet — even in defeat — the professionalism of the troops who had landed at Iwon remained a point of pride. They had done their duty, and they had done it perfectly.

LEGACY AND LESSONS

The landing at Iwon is a reminder that victory and vulnerability often walk hand in hand. It shows the difference between tactical success and strategic wisdom — and how quickly one can overshadow the other.

For decades, the Iwon operation was overshadowed by the famous battles that followed. But in many ways, Iwon represents the essence of the Korean War: a campaign of courage, confusion, and contradiction.

It was a war that swung from near defeat to near victory — and back again — in less than six months. The landing at Iwon sits at the midpoint of that arc, the calm eye of the storm.